Book one. Devil's pit

The action takes place at the end of 1942 in the quarantine camp of the first reserve regiment located in the Siberian military district near the station Berdsk.

Part one

Recruits arrive at the quarantine camp. After some time, the survivors, including Lyosha Shestakov, Kolya Ryndin, Ashot Vaskonyan and Lyokha Buldakov, were transferred to the regiment's location.

The train stopped. Some indifferent evil people in worn military uniforms drove out the recruits from the warm cars and built them near the train, breaking them into dozens. Then, having built into columns, they entered into a semi-dark, frozen basement, where instead of the floor pine paws were scattered on the sand, ordered to be placed on the bunks of pine logs. Submissiveness to fate took possession of Lyosha Shestakov, and when Sergeant Volodya Yashkin appointed him to the first outfit, he took it without resistance. Yashkin was small, thin, angry, had already visited the front, had an order. Here, in the spare regiment, he was after the hospital, and was about to leave again for the front line with the marching company, away from this damn hole so that it burned down, he said. Yashkin went through quarantine, looking around the new recruits - cocks from the gold mines of Baykit, Verkh-Yeniseisk; Siberian Old Believers. One of the Old Believers called himself Kolya Ryndin, from the village of Verkhny Kuzhebar, which stands on the banks of the Amyl River, a tributary of the Yenisei.

In the morning, Yashkin drove the people out into the street - to wash themselves with snow. Lyosha looked around and saw the roofs of the dugouts, a little dusted with snow. This was the quarantine of the twenty-first rifle regiment. Small, single and quadruple dugouts belonged to combat officers, service workers and just idiots in the ranks, without which no Soviet enterprise can do. Somewhere further, in the forest, there were barracks, a club, medical services, a dining room, baths, but the quarantine was at a decent distance from all this so that the recruits would not bring any infection. From experienced people Lyosha learned that they would soon be identified in the barracks. In three months they will undergo military and political training and move to the front - things didn’t matter there. Looking around the filthy forest, Lyosha remembered the native village of Shushikara in the lower Ob.

The guys sucked in my heart because everything around was alien, unfamiliar. Even they, who grew up in barracks, in village huts and in shacks of urban suburbs, were dumbfounded when they saw a feeding place. Behind long stalls nailed to dirty pillars, covered with trough troughs on top, like coffins, military men stood and consumed food from aluminum bowls, holding posts with one hand so as not to fall into deep sticky dirt under their feet. It was called a summer dining room. There were not enough places here, as elsewhere in the Land of Soviets — they fed in turn. Vasya Shevelev, who had time to work as a combine operator on the collective farm, looking at the local order, shook his head and said sadly: "And here's a mess." Experienced fighters chuckled at the newcomers and gave them practical advice.

The recruits were shaved bald. The Old Believers were especially difficult to part with their hair, cried, and were baptized. Already here, in this half-lived basement, the guys were inspired by the significance of what was happening. Political conversations were conducted not by the old, but skinny, with a gray face and a loud voice, captain Melnikov. His whole conversation was so convincing that he could only wonder how the Germans managed to reach the Volga, when everything should be the other way around. Captain Melnikov was considered one of the most experienced political workers in the entire Siberian district. He worked so hard that he had no time to replenish his scanty knowledge.

Quarantine life dragged on. The barracks were not released. In quarantine dugouts, crowding, fights, drinking, theft, stench, lice. No outfits out of turn could establish order and discipline among the rabble of men. Former urki prisoners felt best here. They strayed into artels and robbed the rest. One of them, Zelentsov, gathered around him two orphanages, Grishka Khokhlak and Fefelov; hard workers, former machine operators, Kostya Uvarov and Vasya Shevelev; Babenko respected and fed songs; I didn’t drive Lyosha Shestakova and Kolya Ryndin away from me - they would come in handy. Khokhlak and Fefelov, experienced tweezers, worked at night, and slept during the day. Kostya and Vasya were in charge of food. Lyosha and Kolya sawed and dragged firewood, did all the hard work. Zelentsov sat on the bunk and led the artel.

One evening, the recruits were ordered to leave the barracks, and until late at night kept them in a piercing wind, taking away all their miserable property. Finally, a command was received to enter the barracks, first to the marsheviks, then to the new recruits. The crush began, there was no place. The marching companies took their places and did not let the "Holodrans" in. That vicious, merciless night sank into memory like nonsense. In the morning, the guys arrived at the disposal of the mustachioed foreman of the first company, Akim Agafonovich Shpat. “With these warriors there will be laughter and sorrow for me,” he sighed.

Half of the gloomy, stuffy barracks with three tiers of bunks - this is the abode of the first company, consisting of four platoons. The second half of the barracks was occupied by the second company. All this together formed the first rifle battalion of the first reserve rifle regiment. The barracks, built from the damp forest, never dried out, it was always slimy, moldy from the crowded breath. Four ovens, similar to mammoths, warmed it. It was impossible to warm them up, and it was always damp in the barracks. A weapon rack was leaned against the wall, there were several real rifles and white models made of boards. The exit from the barracks was closed by plank gates, near them an annex. On the left is the captain’s mouth of the foreman of the Spatula, on the right is the daily room with a separate iron stove. All soldier's life was at the level of a modern cave.

On the first day, the recruits were fed well, then they were taken to the bathhouse. Young fighters have amused. There was talk that they would give out new uniforms and even bedding. On the way to the bathhouse, Babenko sang. Lesha still did not know that for a long time now he would not hear any songs in this pit. Improvements in life and service, the soldiers did not wait. Dressed them in old clothes, darned on their stomach. A new, raw bath did not warm up, and the guys completely froze. For two-meter Kolya Ryndin and Lyokha Buldakov, suitable clothes and shoes were not found. Rebellious Lyokha Buldakov threw off his tight shoes and went to the barracks barefoot in the cold.

They didn’t give out bed sheets to the servicemen either, but they kicked them out to drill the next day with wooden mock-ups instead of rifles. In the first weeks of service, the hope in the hearts of people for an improvement in life did not die out. The guys still did not understand that this way of life, not unlike the prison, depersonalizes a person. Kolya Ryndin was born and grew near the rich taiga and the Amyl River. I never knew the need for food. In the army, the Old Believer immediately felt that wartime was a time of hunger. The hero Kolya began to fall off his face, a blush came down from his cheeks, a longing came through his eyes. He even began to forget prayers.

Before the day of the October Revolution, they finally sent boots for large-sized fighters. Buldakov was not pleased here either, he launched shoes from the upper bunks, for which he got into a conversation with captain Melnikov. Buldakov pityingly narrated about himself: he came from the urban village of Pokrovka, near Krasnoyarsk, from early childhood among the dark people, in poverty and work. Buldakov did not report that his father, a violent drunkard, almost did not leave prison, as well as his two older brothers. The fact that he himself had only just turned away from prison by conscription, Lyokha also kept silent, but he was overflowing with the nightingale, telling about his heroic work on the rafting. Then he suddenly rolled his eyes under his forehead, pretending to be fit. Captain Melnikov jumped out of the hut with a bullet, and since then he always looked at Buldakov at political classes with caution. The fighters respected Lyokha for political literacy.

On November 7, a winter dining room was opened. Hungry fighters, holding their breath, listened to Stalin’s speech on the radio. The leader of the peoples said that the Red Army took the initiative in its own hands, because the Country of Soviets had unusually strong rear areas. People piously believed this speech. In the dining room was the commander of the first company, Millet - an impressive figure with a large, bucket-sized face. The company commander did not know much, but they were already afraid. But the deputy company commander of the junior lieutenant Shchus, wounded on Hassan and received the Order of the Red Star there, was accepted and loved immediately. That evening, companies and platoons diverged from the barracks with a friendly song. “Every day Comrade Stalin spoke on the radio, if only there was discipline,” Sergeant Shpator sighed.

The next day, the company’s festive mood passed, pep evaporated. Pshenny himself watched the morning toilet of the fighters, and if someone was cunning, he personally pulled off his clothes and rubbed his face with prickly snow to blood. Petty Officer Shpator only shook his head. The mustachioed, gray-haired, slender, former sergeant major during the imperialist war, Spatore met various animals and tyrants, but he had never seen such a millet.

Two weeks later, the distribution of fighters for special companies took place. Zelentsov was taken to the mortars. Petty Officer Shpator tried his best to sell Buldakov out of his hands, but he was not even taken into a machine gun company. Sitting barefoot on the bunks, this artist read newspapers all day and commented on what he read. The “old men” left over from past marching companies and positively acting on young people were dismantled. In return, Yashkin brought a whole department of newcomers, among whom was a patient who reached the pen, Red Army soldier Poptsov, urinating under himself. The foreman shook his head, looking at the cyanotic kid, and exhaled: "Oh Lord ...".

The foreman was sent to Novosibirsk, and in some special warehouses he found new uniforms for daredevil simulators. Buldakov and Kolya Ryndin had nowhere else to go - they went into operation. Buldakov in every possible way evaded classes and spoiled state property. Shchus realized that he could not tame Buldakov, and appointed him on duty in his dugout. Buldakov felt good at the new post and began to drag everything he could, especially the food. Moreover, he always shared with friends and with the junior lieutenant.

Siberian winter was in the middle. The hardening snowing in the mornings had already been canceled long ago, but still, many fighters managed to catch a cold, a loud cough fell apart at night in the barracks. In the mornings, only Shestakov, Khokhlak, Babenko, Fefelov, sometimes Buldakov and the old Shpator washed themselves. Poptsov no longer left the barracks, lay a gray, wet lump on the lower plank beds. Rose only to eat. They did not take Poptsov to the medical unit; he was already tired of everyone there. Revenues every day became more and more. On the lower bunks lay up to a dozen crouched whining bodies. The merciless lice and night blindness fell upon the servants, hemeralopia was a scientist. Shadows of people roaming around the barracks, wandering around the walls, searching for something all the time.

With incredible resourcefulness of mind, warriors sought ways to get rid of combat training and get something to chew. Someone invented to string potatoes on a wire and put officer chimneys into the pipes. And then the first company and the first platoon were replenished with two personalities - Ashot Vaskonyan and Boyarchik. Both were of mixed nationality: one semi-Armenian semi-Jewish, the other half-Jewish semi-Russian. Both of them spent a month in an officer’s school, reached the pen there, were treated in a medical unit, and from there, they came back a little to a hell of a pit — they would endure everything. Vaskonyan was lanky, skinny, with a pale face, black eyebrows and heavily burr. At the first political lesson, he managed to spoil the work and mood of Captain Melnikov, arguing that Buenos Aires is not in Africa, but in South America.

It was even worse for Vaskonyan in a rifle company than in an officer school. He got there due to a change in the military situation. His father was the chief editor of the regional newspaper in Kalinin, his mother was the deputy department of culture of the regional executive committee of the same city. The domestic, pampered Ashotik was raised by the housekeeper Seraphim. Vaskonyan would lie on the lower planks next to Poptsov, but this eccentric and literate liked Buldakov. He and his company did not allow Ashot to be slaughtered, taught him the wisdom of soldier life, and hid him from the foreman, from Pshenny and Melnikov. For this concern, Vaskoryan told them everything that he managed to read in his life.

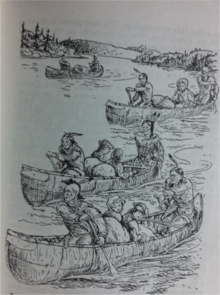

In December, the twenty-first regiment was understaffed - replenishment arrived from Kazakhstan. The first company was instructed to meet them and quarantine them. What the Red Army saw horrified them. The Kazakhs were called up in the summer, in summer uniforms and arrived in the Siberian winter. And already swarthy, the Kazakhs turned black like firebrands. The coughs and wheezing shook the wagons. Under the bunks lay the dead. Arriving at Berdsk station, Colonel Azatyan grabbed his head and ran for a long time along the train, looked into the wagons, hoping at least to see the guys in better condition somewhere, but everywhere there was the same picture. Patients were scattered in hospitals, the rest were scattered in battalions and companies. In the first company, about fifteen Kazakhs were identified. Led over them by a hefty guy with a large face of the Mongolian type named Talgat.

The first battalion, meanwhile, was thrown to roll out the forest from the Ob. The unloading was supervised by Schus, Yashkin helped him. They dwelt in an old dugout excavated on the banks of the river. Babenko immediately began to hunt in the Berdsky bazaar and in the surrounding villages. On the banks of the Oka river gentle regime - no drill. One afternoon, a company spanked into a barracks and ran into a young general on a beautiful stallion. The general examined the haggard, pale faces, and rode along the banks of the Ob, bowing his head and never once looked back at a whistler. The soldiers were not given to know who this forceful general was, but the meeting with him did not pass without a trace.

Another general appeared in the regimental canteen. He swam through the dining room, stirring a spoon with soup and porridge in the basins, and disappeared in the opposite door. The people were waiting for improvement, but none of this followed - the country was not ready for a protracted war. Everything was getting better on the go. The youth of their twenty-fourth year of birth did not withstand the requirements of army life. Feeding in the dining room was scarce, the number of gonads in their mouths increased. The company commander, Lieutenant Pshenny, immediately began to perform his duties.

One chill morning Pshenny ordered every single Red Army soldier to leave the building and build. They even raised the sick. They thought he would see these goners, regret it and return it to the barracks, but Pshenny ordered: “Enough fool! With a song step march to classes! ". Hidden in the middle of the line, the "priests" took a step. Poptsov fell while jogging. The company commander kicked him with a narrow toe of his boot one or two times, and then, furious with anger, he could no longer stop. Poptsov answered each sob with a sob, then stopped sobbing, somehow strangely straightened and died. Rota surrounded the dead comrade. "He killed him!" - exclaimed Petka Musikov, and a silent crowd surrounded Pshenny, throwing up rifles. It is not known what would happen to the company commander, had not intervened in time Shchus and Yashkin.

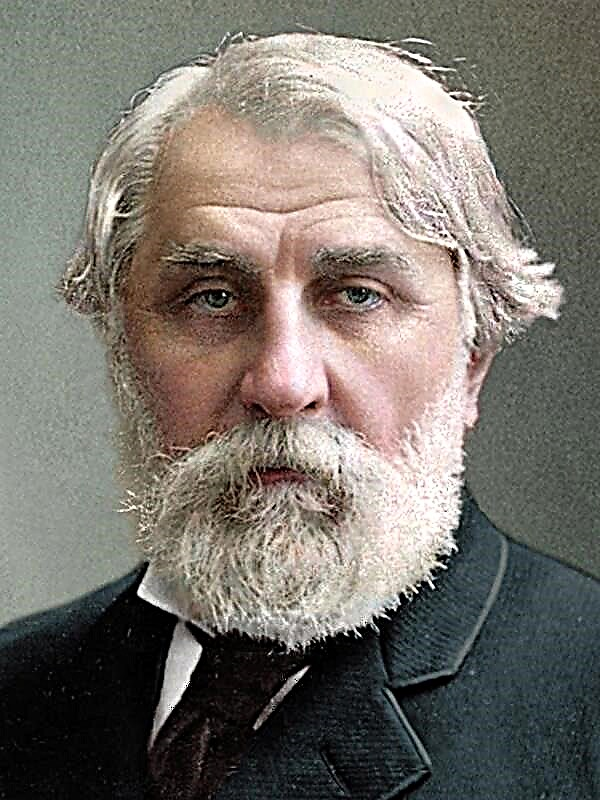

That night Schus could not sleep until dawn. The military life of Alexei Donatovich Schus was simple and straightforward, but earlier, before this life, his name was Platon Sergeyevich Platonov. The surname Shchus was formed from the surname Shchusev - so the clerk of the Trans-Baikal military district heard her. Plato Platonov came from a Cossack family, which was exiled to the taiga.Parents died, and he remained with his aunt-nun, a woman of extraordinary beauty. She persuaded the escort chief to take the boy to Tobolsk, to hand over to the family of pre-revolutionary exiles by the name of Shchuseva, paid for this with herself. The chief kept his word. The Shchusevs - artist Donat Arkadevich and literature teacher Tatyana Illarionovna - were childless and adopted a boy, raised as their own, sent to a military path. Parents died, my aunt got lost in the world - Schus was left alone.

The senior lieutenant of the special department Skorik was assigned to deal with the incident in the first company. She and Schus were once studying at the same military school. Most of the commanders could not stand Schusya, but he was the favorite of Gevorg Azatyan, who always defended him, and therefore could not bother him where necessary.

Discipline in the regiment staggered. Every day it became more and more difficult to manage people. The boys snooped around the regiment in search of at least some food. “Why weren't the guys immediately sent to the front? Why should healthy guys be incapacitated? ” Thought Schus and did not find the answer. During the service he completely reached, stupefied Kolya Ryndin from malnutrition. At first so brisk, he closed himself, fell silent. He was already closer to heaven than to earth, his lips constantly whispered a prayer, even Melnikov could not do anything with him. At night, the dying hero Kolya cried with fear of the impending disaster.

Pomkomvzvoda Yashkin suffered from liver and stomach disease. At night the pain grew stronger, and foreman Spatur smeared his side with ant alcohol. The life of Volodya Yashkin, called eternal pioneer parents in honor of Lenin, was not long, but he managed to survive the battles near Smolensk, the retreat to Moscow, the encirclement near Vyazma, the wound, and the transportation of encircled people from the camp across the front line. Two nurses, Nelka and Faya, pulled him out of that hell. On the way, he contracted jaundice. Now he felt that he was soon facing the road to the front. With his straightforwardness and inanimate character, he did not cling to the rear for health reasons. His place where there is last justice is equality before death.

This marching course of army life was shaken by three major events. First, an important general arrived at the twenty-first rifle regiment, checked the soldier's food, and arranged a delivery to the cooks in the kitchen. As a result of this visit, the potato peeling was canceled, due to this, the portions increased. A solution came out: to fighters under two meters and above give an additional portion. Kolya Ryndin and Vaskonyan with Buldakov came to life. Kolya still moonlighted in the kitchen. All that he was given for this, he shared on a crust between friends.

Announcements appeared on the club’s billboards, informing them that on December 20, 1942, a demonstration trial of a military tribunal over K. Zelentsov was held at the club. No one knew what this rogue had done. It all started not with Zelentsov, but with the artist Felix Boyarchik. Father left only a surname for Felix. Mom, Stepanida Falaleevna, a masculine woman, an iron Bolshevik, was found in the field of Soviet art, shouting slogans from the stage to the sound of a drum beat, to the sound of a trumpet, with the construction of pyramids. When and how she got a boy, she almost did not notice. Serve Stepanida to old age in the district House of Culture, if the trumpeter Boyarchik hadn’t done anything and thundered in prison. Following him, Styopa was thrown into the Novolyalinsky timber industry. She lived there in a barrack with the family women who raised Felu. Most of all he regretted the large Theokla the Blessed. It was she who thought Styopa to demand a separate house when she became an honored worker in the field of culture. In this house, in two halves, Styopa settled with the blessed family. Theokla became the mother for Felix, and she also escorted him to the army.

In the Lespromkhoz House of Culture, Felix learned to draw posters, signs and portraits of leaders. This skill was useful to him in the twenty-first regiment. Felix gradually moved to the club and fell in love with the girl-ticketer Sophia. She became his unmarried wife. When Sophia became pregnant, Felix sent her to the rear, to Thekla, and an uninvited guest Zelentsov settled in his side. He immediately began to drink and play cards for money. Felix could not expel him, no matter how he tried. Once, Captain Dubelt looked into the kapterka and discovered Zelentsov sleeping behind a stove. Dubelt tried to grab him by the scruff of his neck and take him out of the club, but the fighter did not give in, hit the captain with his head and broke his glasses and nose. It’s good that he didn’t kill the captain - Felix called the patrol on time. Zelentsov turned the court into a circus and a theater at the same time. Even the experienced chairman of the tribunal Anisim Anisimovich could not cope with him. I really wanted Anisim Anisimovich to sentence the obstinate soldier to be shot, but I had to confine myself to a penalty company. Zelentsov was escorted as a hero by a huge crowd.

Part two

Demonstrative executions begin in the army. For escaping to death, the innocent Snegirev brothers are sentenced. In the middle of winter, the regiment is sent to harvest grain to the nearest collective farm. After that, in early 1943, rested soldiers sent to the front.

Suddenly, Skorik came to the dugout of the second lieutenant Schusya late in the evening. Between them a long, frank conversation took place. Skorik informed Shchus that a wave of order number two hundred twenty-seven had reached the first regiment. Demonstration executions began in the military district. Schus did not know that Skorik was called Lev Solomonovich. Skorik's dad, Solomon Lvovich, was a scientist, wrote a book about spiders. Mom, Anna Ignatyevna Slokhova, was afraid of spiders and didn’t let Leva approach them. Leva was in his second year at the university, at the faculty, when two military men came and took his father away, mother soon disappeared from the house, and then they pulled him into the office of Leva. There he was intimidated and he signed a renunciation of his parents. Six months later, Leva was again called to the office and informed that an error had occurred. Solomon Lvovich worked for the military department and was so classified that the local authorities did not know anything and shot him along with the enemies of the people. Then they took away and, most likely, shot Solomon Lvovich’s wife to cover his tracks. His son was apologized and allowed to enter a military school of a special nature. Lyova’s mother was never found, but he felt that she was alive.

Lyosha Shestakov worked with the Kazakhs in the kitchen. Kazakhs worked together and learned to speak Russian in the same friendly manner. Lesha still did not have so much free time to remember his life. His father was from exiled special settlers. He snatched Antonin’s wife in Kazym-Cape; she was from a semi-Khatyn-semi-Russian clan. Father was rarely at home - he worked in a fishing team. His character was heavy, unsociable. One day, father did not return on time. Fishing boats, having returned, brought the news: there was a storm, a team of fishermen drowned and with it the foreman Pavel Shestakov. After the death of his father, his mother went to work in Rybkoop. Oskin, a fish receiver frequented throughout the Ob, was known as a dumbass nicknamed Gerka - a mountain poor. Lyosha threatened his mother that he would leave home, but nothing had any effect on her, she even became younger. Soon Gerka moved to their house. Then two little sisters were born at Lesha: Zoyka and Vera. These creatures evoked some unknown kindred feelings in Leshka. Leshka went to war after Gerka, the mountain poor. Most of all Lesha missed his sisters and sometimes remembered his first woman, Tom.

Discipline in the regiment fell. We survived to an emergency: twin brothers Sergei and Yeremey Snegirev left the second company. They were declared deserters and searched wherever possible, but were not found. On the fourth day, the brothers themselves appeared in the barracks with bags full of food. It turned out that they were with her mother, in her native village, which was not far from here. Skorik clutched his head, but he could no longer help them. They were sentenced to death. The regiment Gevorg Azatyan made sure that only the first regiment was present during the execution. The Snegirev brothers did not believe to the very end that they would be shot, thought that they would be punished or sent to the penal battalion as Zelentsova. Nobody believed in the death penalty, not even Skorik. Only Yashkin knew that the brothers would be shot - he had already seen this. After the shooting, the barracks was seized with bad silence. “Damned and killed! All!" - rumbled Kolya Ryndin. At night, drunk to insensibility, Schus was eager to fill the face of Azatyan. Senior Lieutenant Skorik drank lonely in his room. The Old Believers united, drew a cross on paper and, led by Kolya Ryndin, prayed for the repose of the souls of the brothers.

Skorik again visited the dugout Shchusya, said that immediately after the New Year the army would introduce epaulettes and rehabilitate the people's and tsarist times of the commanders. The first battalion will be thrown to the harvest and will remain on collective farms and state farms until sent to the front. In these unprecedented works - in the winter threshing of bread - the second company is already located.

In early January 1943, soldiers of the twenty-first regiment were given epaulettes and sent by train to Istkim station. Yashkin was determined to be treated at a district hospital. The rest went to the Voroshilov state farm. The director of the company, Ivan Ivanovich Tebenkov, caught the company moving to the state farm; he took Petka Musikov, Kolya Ryndin and Vaskonyan with him, and provided the rest with logs full of straw. The guys settled in the huts in the village of Osipovo. Shchusya was settled in a barrack near the head of the second department, Valeria Methodievna Galusteva. She took in the heart of Schusya a separate place, which until now had been occupied by his missing aunt. Lyosha Shestakov and Grisha Khokhlak fell into the hut of the old Zavyalovs. After some time, the drunken soldiers began to pay attention to the girls, and it was then that Grishka Khokhlak’s ability to play the button accordion came in handy. Almost all the soldiers of the first regiment were from peasant families, they knew this work well, they worked quickly and willingly. Vasya Shevelev and Kostya Uvarov repaired the collective farm combine, on it they threshed the grain, which was kept in shovels under the snow.

Vaskonian came to the cook Anka. Anka did not like the strange books, and the guys exchanged him for Kolya Ryndin. After that, the quality and calorie content of the dishes improved dramatically, and the soldiers thanked the hero Kolya for this. Vaskonyan also settled with the old Zavyalovs, who greatly respected him for his scholarship. And after some time, her mother came to Ashot - in this she was helped by the regiment Gevorg Azatyan. He hinted that he could leave Vaskonyan at the headquarters of the regiment, but Ashot refused, said he would go to the front with everyone. He was already looking at his mother with different eyes. Leaving in the morning, she felt that she was seeing her son for the last time.

A few weeks later, an order came back to the location of the regiment. It was a short, but soul tearing parting with the village of Osipovo. They did not have time to return to the barracks - immediately a bathhouse, new uniforms. Petty Officer Shpator was pleased with the rested fighters. That evening Lyosha Shestakov heard a song for the second time in the barracks of the twenty-first rifle regiment. The marching companies were received by General Lakhonin, the same one who had once met the Red Army men wandering the field, and his longtime friend Major Zarubin. They insisted that the weakest fighters be left in the regiment. After a lot of abuse, about two hundred people remained in the regiment, of which half of the terminally ill will be sent home to die. The twenty-first rifle regiment easily got off. With their companies, the entire command of the regiment was sent to positions.

Marching companies were reduced in the military camp of Novosibirsk. Valeria Mefodevna came into the first company, brought greetings and nods from Osipov’s chills and owners and a small bag full of all kinds of food. The regiment, on alert, was taken out of the barracks at dawn. After the speeches of numerous speakers, the regiment set off. Marching companies led to the station in a roundabout way, in the dull marginal streets. They met only a woman with an empty bucket. She rushed back to her courtyard, threw buckets and sweepingly baptized the army afterwards, parting of the successful conclusion of the battle of her eternal defenders.

The second book. Bridgehead

The second book briefly describes the events of winter, spring and summer of 1943. Most of the second book is devoted to the description of the crossing of the Dnieper in the autumn of 1943.

Part one. On the eve of the crossing

After spending spring and summer in battles, the first rifle regiment was preparing for the crossing of the Dnieper.

On a transparent autumn day, the advanced units of two Soviet fronts reached the banks of the Great River - the Dnieper. Lyosha Shestakov, collecting water from the river, warned the newcomers: there is an enemy on the other side, but you can’t shoot at him, otherwise the whole army will be left without water. There was already such a case on the Bryansk Front, and on the banks of the Dnieper there will be everything.

The artillery regiment in the rifle division arrived at the river at night. Somewhere close was the rifle regiment, in which the first battalion was commanded by Captain Schus, the first company - Lieutenant Yashkin. Here, the company commander was Kazakh Talgat. Platoons were commanded by Vasya Shevelev and Kostya Babenko; Grisha Khokhlak with the rank of sergeant commanded the squad.

Arriving in the Volga region in the spring, Siberians stood for a long time in the empty looted villages of the Volga Germans who were killed and deported to Siberia. Lyosha, as an experienced signalman, was transferred to the howitzer division, but he did not forget the guys from his company. The General Lakhonin’s division took the first battle in the Zadonskaya steppe, standing in the way of German troops breaking through the front. Losses in the division were not noticeable. The division commander liked the army very much, and he began to keep it in reserve - just in case. Such a case occurred near Kharkov, then another state of emergency near Akhtyrka. Lyosha received the second order of World War II for that battle. Colonel Beskapustin treasured Kolya Ryndin, sent him to the kitchen all the time. Vaskoryan left at the headquarters, but Ashot dared to the chiefs and stubbornly returned to his native company. Schusya hurt the Don, he was commissioned for two months, went to Osipovo and created Valeria Methodievna another child, this time a boy. He also visited the twenty-first regiment, visiting Azatyan. From him, Shchus learned that foreman Shpator died on the way to Novosibirsk, right in the car. He was buried with military honors in the regimental cemetery. The spatula wanted to lie next to the Snegirev brothers or Poptsov, but their graves were not found. After the cure, Schus came to Kharkov.

The closer the Great River became, the more soldiers in the Red Army who did not know how to swim became. Behind the front, a monitoring army is moving, washed, well-fed, vigilant of days and nights, suspecting everyone. The deputy commander of the artillery regiment, Alexander Vasilyevich Zarubin, again sovereignly ran the regiment. His long-time friend and accidental relative was Prov Fedorovich Lakhonin. Their friendship and kinship were more than strange. With his wife Natalia, the daughter of the head of the garrison, Zarubin met on vacation in Sochi. They had a daughter, Ksyusha. The old people raised her, since Zarubin was transferred to a distant region. Soon Zarubin was sent to study in Moscow. When he returned to the garrison after a long training, he found a one-year-old child in his house. The culprit was Lahonin. The opponents managed to remain friends. Natalya wrote letters to the front to both her husbands.

In preparation for crossing the Dnieper, the soldiers rested, flopped all day in the river. Schus, looking through the binoculars on the opposite, right, coast and left-bank island, could not understand: why they chose this bad place for the crossing. Schustch gave the Shestakov a special task - to establish communication across the river. Lyosha arrived at the artillery regiment from the hospital. He came to that point that he could not think of anything but food. On the very first evening, Leshka tried to steal a couple of crackers, was caught with the red-handed colonel Musyonok and taken to Zarubin. Soon the major allocated Leshka, put on the phone at the regiment headquarters.Now Leshka needed to get at least some watercraft in order to transport heavy coils with communications to the right bank. He found a half-bent boat in a well about two miles from the shore.

Rested people could not sleep, many foresaw their death. Ashot Vaskonyan wrote a letter to his parents, making it clear that this is most likely his last letter from the front. He did not indulge his parents with letters, and the more he converged with the “fighting family”, the more he moved away from his father and mother. Vaskonyan was a little in battles, Schus took care of him, pushed him somewhere to the headquarters. But from such a tricky place, Ashot rushed to his home. Schusu also could not sleep, he again and again wondered how to cross the river, while losing as few people as possible.

In the afternoon, at an operational meeting, Colonel Beskapustin gave the task: the first reconnaissance platoon should go to the right bank. While this platoon of suicide bombers will distract the Germans, the first battalion will begin the crossing. Having reached the right bank, people along ravines will advance deep into the enemy’s defense as stealthily as possible. By morning, when the main forces cross, the battalion should engage in battle in the depths of the German defense, in the vicinity of the height of One Hundred. The company of Oskin, nicknamed Gerka - a mountain poor, will cover and support the battalion of Schusya. Other battalions and companies will begin to cross on the right flank to give the impression of a mass attack.

Many did not sleep that night. The soldier Teterkin, who fell into a pair with Vaskonyan, and since then dragging along behind him, like Sancho Panza after his knight, brought hay, laid Ashot down and laid down next to him. Another couple peacefully cooed in the night - Buldakov and Sergeant Finifatiev, who met in the military echelon along the road to the Volga. Distant explosions were heard in the night: the Germans blew up the Great City.

The fog lasted a long time, helping the army, prolonging the lives of people by almost half a day. As soon as it got light, shelling began. A reconnaissance platoon started a battle on the right bank. Stormtrooper squadrons passed overhead. Conditional rockets poured out of the smoke - rifle companies reached the right bank, but no one knew how much was left of them. The crossing began.

Part two. Crossing

The crossing brought huge losses to the Russian army. Lesha Shestakov, Kolya Ryndin and Buldakov were injured. This was a turning point in the war, after which the Germans began to retreat.

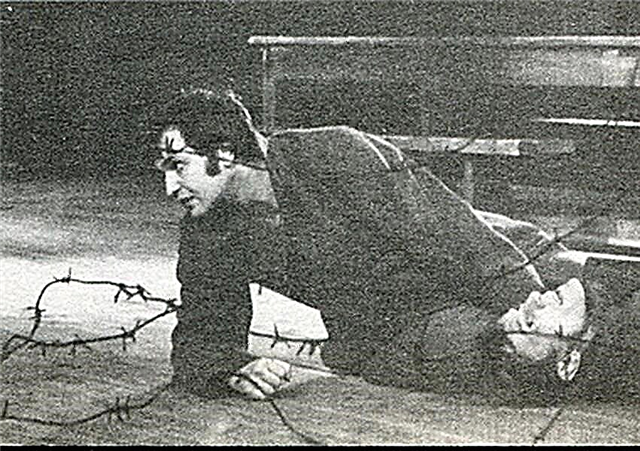

The river and the left bank were covered with enemy fire. The river was boiling, full of dying people. Those who could not swim clung to those who knew how, and dragged them under water, turned shaky rafts made of raw wood. Those who returned to the left bank, to their own, were met by the valiant fighters of the overseas detachment, shot people, pushed back into the river. The Schusya battalion was one of the first to cross, and delved into the ravines of the right bank. Leshka began to cross with his partner Syoma Prakhov.

If there were units well trained, able to swim, they would have reached the coast in combat. But on the island across the river came people who had already swallowed water, drowned weapons and ammunition. Having reached the islands, they could not budge and died under machine-gun fire. Lyosha hoped that the Schusya battalion left the island before the Germans set it on fire. He slowly sailed downstream below the general crossing, unwinding the cable - it was barely enough to reach the opposite bank. On the way, I had to fight off drowning people who strove to turn over a flimsy boat. On the other bank, Major Zarubin was already waiting for Leshko. Communication across the river was established, and the wounded Zarubin immediately began to give tips for artillery. Soon, fighters who survived the morning crossing began to gather around Zarubin.

The crossing continued. The advanced units lurked along the ravines, trying to establish a connection with each other until dawn. The Germans concentrated all the fire on the right-bank islet. Rota Oskina, who retained the backbone and ability to perform a combat mission, reached the right bank. Oskin himself, wounded twice, the soldiers tied to a raft and allowed to flow. He was a lucky man - he got to his own. From the mouth of the Cherevinka River, where Leshka Shestakov landed, to the crossed Oskin company, there are three hundred fathoms, but not fate.

It was expected that the penalty company would be thrown into the fire first, but she began to cross already in the morning. Above the coast, called the bridgehead there was nothing to breathe. The battle calmed down. Thrown back to the Hundred altitude, the thinned enemy units no longer attacked. Penalties crossed almost without loss. Far from everyone, a boat was crossing the river under the command of military assistant Nelka Zykova. Faya was on duty at the medical post on the left bank, and Nelka transported the wounded across the river. Among the penalties was Felix Boyarchik. He helped convicted Timofei Nazarovich Sabelnikov bandage the wounded. Sabelnikov, the chief surgeon of the army hospital, was tried for the death of a mortally wounded man on his table, during an operation. A fine company entrenched along the coast. Food and weapons were not issued to fines.

The battalion of captain Schusya was scattered over the ravines and secured. Scouts established contact with the regiment headquarters and picked up the remnants of platoons and companies. Found and the remains of the company Yashkina. Yashkin himself was also alive. Their task was simple: to go as deep as possible along the right bank, gain a foothold and wait for the partisans to strike from the rear and the landing from the sky. But there was no connection, and the battalion commander understood that the Germans would cut off his battalion from the crossing. At dawn it was calculated: four hundred and sixty people were digging in at a slope of a height of One Hundred - all that remained of three thousand. Scouts reported that Zelentsov had a connection. Schus sent three signalmen to him. Schus remembered two, and the third - Zelentsov, who now became Shorokhov - did not recognize.

Shestakov pushed the boat below the mouth of Cherevinka, behind the toe, and with relief returned under the yar where the soldiers dug in, digging in the high slope of the mink. Finifatiev almost brought a longboat full of ammunition to the right bank, but put it aground. Now it was necessary to get this longboat. There came signalmen from Colonel Beskapustin, who, as it turned out, was not far from Cherevinka. The longboat was dragged away at the mouth of the rivulet in the morning until the fog cleared. At sunrise, Nelya and Fay arrived for the wounded Zarubin, but he refused to swim, and remained waiting for a replacement.

The command clarified intelligence and snickered. It turned out: they repulsed from the enemy about five kilometers of coast in width and up to a kilometer in depth. The valiant commanders spent tens of thousands of tons of ammunition, fuel, and twenty thousand people killed, drowned, and wounded. The losses were overwhelming.

Lyosha Shestakov went to the water to wash himself and met Felix Boyarchik. After some time, Boyarchik and Sabelnikov were guests of the Zarubin detachment. The boyar was wounded in the Oryol region, he was treated in the Tula hospital, and there he was sent to a transit point. From there, Felix landed at the gunners, in the platoon of control of the fourth battery. Recently, the artillery brigade left the battle, where it lost two guns, the third gun was separated from the battery, hidden in the bushes. In a Soviet country, cars were always valued more than human life, so commanders knew that they would not be praised for their lost guns. The battery was written off two guns, and the third rusted in the bushes without a wheel. The battery commander “discovered” the missing wheel when Boyarchik was on guard. So Felix fell under the tribunal, and then in the penalty company. After everything experienced, Felix did not want to live.

At night, on two pontoons, a select foreign squadron armed with new machine guns was transported to the bridgehead. Ammunition and weapons were transported along with the detachment - for the contingent convicted of atonement for their blood. They forgot to transport food and medicines. Unloading, the pontoons quickly set off - too many important things were waiting for the warriors across the river across the river.

The Ostseans Hans Holbach and the Bavarian Max Kuzempel have been partners since the start of the war. Together they fell into Soviet captivity, together they fled from there, due to the stupidity of Holbach they fell back to the front. When the fines were sent into battle, Felix Boyarchik shouted: “Kill me!” rushed right into the trench to these Germans. Felix was not killed, he ended up in captivity, although he struggled to die. One of the first in this battle was Timofey Nazarovich Sabelnikov.

This day was especially troubling for Schusya. After breaking the penalty company, the Germans began the liquidation of the partisan detachment. The battle lasted for two hours, toward its end the aircraft buzzed in the sky, and the landing began. This operation was carried out so mediocre that a select, carefully trained airborne detachment of 1800 people died without ever reaching the ground. Schus understood that now the Germans would take up his detachment. Soon he was informed that Kolya Ryndin was seriously wounded. I clicked on the phone and called Lyosha Shestakova and ordered him to transport Kolya to that shore. A whole compartment was dragging Kolya Ryndin to the boat. Vaskonyan pushed the boat away and stood on the shore for a long time, as if saying goodbye. Bailing to the left bank, Leshka barely carried the wounded to medical battalion.

Leshkino journey across the river did not go unnoticed. Almost all telephone lines laid from the left bank were silent. The communications chief ordered Shestakov to transfer communications from one coast to another. Major Zarubin understood that Leshka was forced to do someone else's work, but said nothing, leaving the soldier to decide for himself. Taking a few wounded into the boat, Leshka hardly reached the left bank. They gave him a coil of cable and two assistants who could not swim. When they sailed back, it was already light. The Germans began shelling the boat as soon as it was in the middle of the river, where the fog had already risen. The rotten, fragile little vessel turned upside down, Lyoshkin's aides immediately went down, Lesha himself managed to sail to the side. He struggled with his legs, trying to get to the shore and not think about the dead who are at the bottom of the river. Of the last forces, Leshka reached the sandy shore. Two fighters grabbed his hands, dragged him under the cover of a yar. Left to his own devices, Shestakov crawled into cover and lost consciousness. Lech Buldakov took care of him.

Opening his eyes, Shestakov saw the face of Zelentsov-Shorokhov in front of him. He said that there was a battle under the height of One Hundred Germans finish off the battalion Schusya. Having risen, Leshka reported to Zarubin that it was not possible to establish a connection, and asked permission to withdraw for a short while. Where and why - the major did not ask. Lyosha crossed Cherevinka and began to quietly make his way upstream. Further along the ravine Leshka discovered a German observation post. A little further he discovered the place where the Russian detachment stumbled upon the Germans. Among the dead were Vaskonyan and his faithful partner Teterkin.

Meanwhile, Lieutenant Colonel Slavutich came to Zarubin. He asked the major to give him people to take the German observation post. Zarubin sent Finifatyev, Mansurov, Shorokhov, and Shestakov arrived in time. During this operation, Lt. Col. Slavutich and Mansurov died, Finifatiev was wounded. From the captured Germans they learned that the enemy headquarters was located in the village of Velikiy Krinitsy. At half past four the artillery raid to the height of One hundred began, guns bombed the village, turning it into ruins. By evening, the height was taken. The chief of staff Ponayotov moved to the right bank - to replace Zarubin, brought some food. They carried the major into the boat; he himself no longer had the strength to go. The wounded sat and lay all night on the shore, hoping that the boat would come behind them.

Nelka Zykova’s father, a boiler-maker from the Krasnoyarsk locomotive depot, was declared an enemy of the people and shot without trial. Mother, Avdotya Matveevna, was left with four daughters. The most beautiful and healthy of them was Nelka. The godfather Nelka, doctor Porfir Danilovich, attached her to nursing courses. Nelka came to the front immediately after the outbreak of war and met Faya. Fay had a terrible secret: her whole body, from her neck to her ankles, was covered with thick hair. Her parents, artists of the regional operetta, nonchalantly called Fayu a monkey. Neli fell in love with Faya as a sister, took care of and protected her as best she could. Faya could no longer do without a friend.

At night, Shorokhov replaced Shestakov by the phone. In the war, Shorokhov felt good, as if he had embarked on a risky business. He was the son of a dispossessed peasant Markel Zherdyakov from the Pomeranian village Studenets. It was imprinted in the far corner of the memory: he was running, Nikita Zherdyakov, behind the cart, and his father was pushing the horse. He was picked up by the workers of the peat procurement village, given a shovel. After working for two years, he fell into the company of criminals-thugs, and off we go: prison, stage, camp. Then escape, robbery, the first murder, again prison, camp. By this time, Nikitka had become a camp wolf, changed several names - Zherdyakov, Cheremnykh, Zelentsov, Shorokhov. He had one goal: to survive, get the tribunal judge Anisim Anisimovich and put a knife into his enemy.

Soon, a hundred fighters, several boxes of ammunition and grenades, and some food were transported to the bridgehead. All this was claimed by Beskapustin. Schus took a strong dugout, recaptured from the Germans. He understood that this was not for long. In the morning the Germans began to encroach on the Schusya battalion, with which a temporary connection was established, cutting off the siding to the river. And at this disastrous hour, the bleating voice of the head of the political department, Lazar Isakovich Musyonok, came across the river. Occupying a precious connection, he began to read an article from the newspaper Pravda. The first could not stand Schus. To prevent conflict, Beskapustin intervened, disconnected the line.

The day passed in continuous battles. The enemy cleared the height of Hundred, crowded out a rare Russian army. A large army was accumulating on the left bank, but for what - no one knew. The morning was bustling. Somewhere in the upper reaches of the river, the Germans gouged a barge with sugar beets, with the flow of vegetables they nailed to the bridgehead and in the morning “harvesting” began. All day there were fights in the air over the bridgehead. The remnants of the first battalion got especially strong. Finally, the long-awaited evening sank to the ground. The head of the political department of the division, Musyonok, was allowed to work with the recalcitrant shore. This man, being in the war, did not know it at all. Beskapustin of the last forces restrained his commanders.

Lyokha Buldakov could only think of food. He tried to remember his native Pokrovka, his father, but again his thoughts turned to food. Finally, he decided to get something from the Germans and resolutely stepped into the darkness. At the deadliest hour of the night, Buldakov and Shorokhov fell into Cherevinka, dragging three German satchels full of provisions with them, divided it into all.

In the morning, the Germans stopped active operations. They demanded from the headquarters of the division to restore the situation. At the end of the forces, Colonel Beskapustin decided to counterattack the enemy. Ranks from the regiment headquarters, swearing loudly, gathered people along the shore. Buldakov did not want to leave Finifatiev, as if he felt that he would not see him again. During the daytime bombardment, the donkey settled on the high bank of the river and buried hundreds of people underneath, and Finifatiev died there.

At first, Beskapustin's regiment was successful, but then the Beskapustinians ran into the mined slope of the Hundred altitude. The soldiers dropped their weapons and rushed back to the river. By the end of the second day, Beskapustin had only about a thousand healthy soldiers, and Shchusya in the battalion with half a thousand. At noon, the attack began again. If Buldakov’s boots fit, he would have run to the enemy machine gun for a long time, but he was in tight boots tied to the legs with twine. Lyokha fell into the machine-gun nest from the rear. Without disguise, he went to the sound of a machine gun and was so focused on the target that he did not notice a niche covered by a raincoat. A German officer jumped out of a niche and unloaded a pistol clip into Buldakov’s back. Lyokha wanted to rush at him, but lost a precious moment due to tight shoes.Hearing the shots from behind, an experienced pair of machine gunners - Holbach and Kuzempel - thinking that the Russians had bypassed them, rushed to the door.

Buldakov was alive and began to feel himself. The past day of the bridgehead was somehow especially psychotic. There were many unexpected fights, unjustified losses. Despair, even insanity, swept the warriors on Velikokrynitsky bridgehead, and the forces of the warring parties were already running out. Only obstinacy forced the Russians to hold onto this riverbank. In the evening, rain poured over the bridgehead, which revived Buldakov, gave him strength. He rolled with a groan on his stomach and crawled to the river.

An impenetrable cloud of lice covered people on the bridgehead. The heavy smell of decaying drowned people floated over the river in a thick cloud. One hundred had to leave the height again. The Germans beat everything that tried to move. And on the still working communication line, they asked to be patient. Night fell, Shestakov stepped on another duty. The Germans densely fired along the front line. Lesha has already stepped on the line several times - disconnected. When he once again restored the line, he was brushed aside by a mine explosion. Leshka did not reach the bottom of the ravine, fell on one of the ledges and lost consciousness. In the morning, Shorokhov discovered that Leshka was gone. He found Shestakov in a ravine. Lyosha was sitting, clutching the end of the wire in his fist, his face was disfigured by an explosion. Shorokhov re-established communication, returning to the telephone, reported to Ponayotov that Leshka was dead. Ponayotov chased the stubborn Shorokhov behind Leshka, and ensured that a boat was sent from the other side for the wounded. Nelka quickly organized the crossing. After some time approaching the boat, she found a wounded man there. He was lying, throwing his arms overboard. It was Buldakov. Despite the overload, Nelya took him with her.

Around noon, up along the river, about ten kilometers from the bridgehead, artillery fire began. The Soviet command once again launched a new offensive, taking into account previous mistakes. This time a powerful blow was dealt. On the river began the construction of the crossing. What began in the newspapers was called the Battle of the River. At dawn below the river, a crossing also started. The remnants of the units of the Velikokrynitsky bridgehead were ordered to join the neighbors. Everyone who could move went into battle. Shchus walked ahead with a gun in his hands. Fighters of a new bridgehead poured towards them in a crowd.

In the farmhouse, where several burned-out huts remained, soldiers were given food, tobacco, soap. Having tied a shortened cloak-tent under the stigma, a Musyonok flew along the shore. On the outskirts of the farm, in an empty half-burnt hut, the officers who survived the battles were sleeping on straw. The little musk flew in and here, made a scandal over the lack of sentries. Schus could not stand it, again rude to the head of the political department of the division. As a correspondent for Pravda, Musyonok wrote various articles about the enemies of the people, and drove a lot of people to the camps. In the division, Musyonka was hated and feared. He knew this very well and climbed into every hole. The Musyonok lived royally, he had four cars at his disposal. In the back of one of them was housing, where the typist Izolda Kazimirovna Kholedyskaya, a beauty from a repressed Polish family, who already had the Order of the Red Star and the medal "For Military Merit," was hosted. Nelka had only two medals “For Courage”.

Reporting to Schusya, the military commander, as a boy, Musyonok could not stop at all. He did not see the captain's glassy eyes and his face twisted by a cramp. Comrade Musyonok poorly knew these stubborn laborer-officers. If I knew, I would not have climbed into this hut. But Beskapustin knew them well, and he did not like the gloomy silence of Schusya. Some time later, Shchus found Musyonka's car. His driver Brykin fiercely hated his boss, and at the request of Schusya willingly went away for the gas key all night. Late in the evening, Shchus returned to the car and found that Musyonok was already sleeping sweetly. Schus climbed into the cab and drove straight to the minefield. He chose a cool dodger, dispersed the car and jumped easily. A powerful explosion thundered. Schus returned to the hut and calmly fell asleep.

On the right bank of the river, fallen soldiers were buried, and countless corpses were dragged into a huge pit. On the left bank there was a magnificent funeral of the deceased head of the political department of the guard division. Next to the luxurious gilded coffin stood Isolda Kazimirovna in a black lace shawl. Chamber music and heard speeches sounded. A hill with a heap of flowers and a wooden obelisk grew over the river. Over the river, new pits filled up with a human mess. A few years later, a man-made sea will appear on this place, and pioneers and war veterans will lay wreaths at the grave of Musyonok.

Soon, Soviet troops will cross the Great River and connect all four bridgeheads. The Germans will draw their main forces here, while the Russians will break through the front far from these four bridgeheads. Wehrmacht troops will still go on the counterattack. Hard hit the Lachonin’s corps. Lakhonin himself will receive the post of army commander and will take Schusya’s division under his wing. Colonel Beskapustin Avdey Kondratievich will be promoted to general. Nelka Zykova will be wounded again. In her absence, Faith’s faithful girlfriend will lay hands on herself. Komroty Yashkin and Lieutenant Colonel Zarubin will receive the title of Heroes and will be commissioned for disability. By bleeding the enemy in the autumn battles, two powerful fronts will begin a deep coverage of enemy troops. Retreat in winter conditions will turn into a stampede. Hungry, sick, covered with a cloud of lice, the strangers will die in the thousands, and finally they will be crushed, crushed by caterpillars of tanks, and the Soviet troops pursuing them to smash them to pieces.